In the early days of the modern Olympic Games, from 1912 to 1948, a fascinating convergence of athleticism and culture unfolded as art competitions took center stage alongside the sporting spectacles, creating an extraordinary union of physical prowess and artistic expression.

The idea of including art in the Olympics was championed by Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the modern Olympic Movement. Coubertin believed that art was an essential component of a well-rounded education, and he saw the Olympics as an opportunity to promote artistic expression alongside athletic achievement.

The art competitions encompassed a wide range of categories, including architecture, painting, sculpture, literature, and music. Each submitted piece had to draw inspiration from sports and had to be previously unpublished. Artists from around the world submitted their sport-inspired works for consideration, and medals were awarded to the winners in each category. Interestingly, if judges couldn't determine a clear winner, they would not award gold medals, and in some cases only a bronze medal was awarded. Over the years, it became clear that art was not as easy to judge as sports.

Despite their initial popularity, the art competitions eventually fell out of favour with Olympic organisers. Critics argued that art was subjective and therefore difficult to judge in a fair and consistent manner. Additionally, there were concerns that many participants were professional artists or established in their fields. This went against the idea behind the Olympics as an amateur event.

As a result, the art competitions were discontinued after the 1948 Olympics in London. The legacy of Olympic art competitions highlights the importance of artistic expression, emphasising that the essence of art transcends judgment and competition, serving as a powerful medium for communication, reflection, and connection.

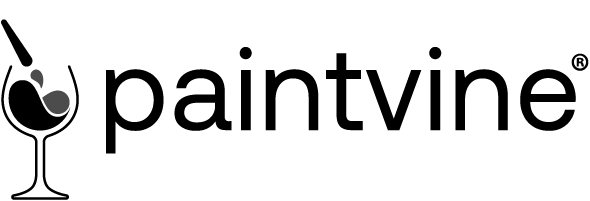

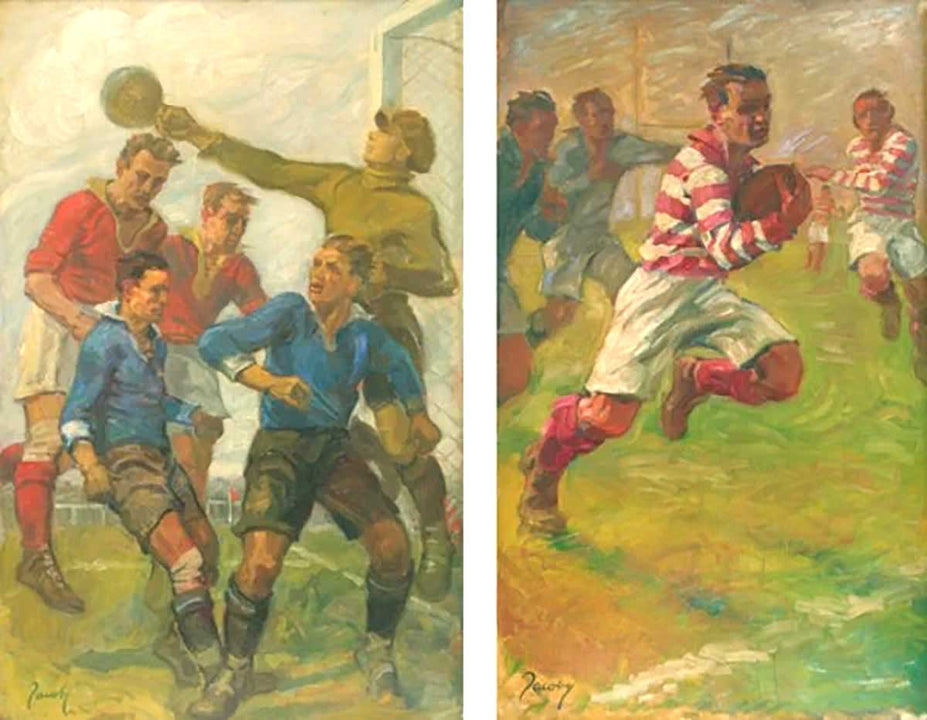

Pictured is Jean Jacoby’s paintings Corner (left), and Rugby (right). Rugby won gold at the 1928 Olympic Art Competitions in Amsterdam. Image from Smithsonian.com.